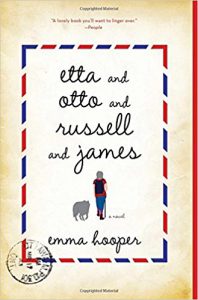

Etta and Otto and Russell and James, by Emma Hooper

Etta and Otto and Russell and James

By Emma Hooper

Simon & Schuster

Five stars

Reviewed by Jessica Gribble

Etta and Otto and Russell and James has taught me that not enough books take elderly people seriously, that I might have to give magical realism a second chance, and that author Emma Hooper can capture the important moments of relationships and feelings in just a few perfectly structured sentences.

Etta leaves Otto a note and starts walking. She’s going to see the sea, which Otto saw in the war. We learn in bits and pieces about her state of mind and her mental state, perhaps most from the first line of the note she’s carrying: Etta Gloria Kinnick of Deerdale farm. 83 years old in August. The rest of the note lists her family, though Russell is technically an old friend.

This book is simple and spare and deep all at the same time. It has some resemblance to Cormac McCarthy’s work, not least because it doesn’t use quotation marks for dialogue, which makes you feel like you’re floating through the text. You can’t look away because you’ll lose your place, so you just keep going. The book’s four main characters, those named in the title, are all it needs.

The structure of this book is a lot like sitting down to interview your grandmother. The memories aren’t in order, and they come and go. We learn what it’s like for Etta to travel on foot, skirting lakes and towns, eating little and sleeping outside. We also learn how she became a schoolteacher and met Otto and Russell; they were her students in one little room until Otto left for the war and Russell couldn’t.

We learn what it’s like to be Otto, waiting for Etta to find the sea. Learning to bake and becoming an artist. Trying to find a way to sleep. Looking for comfort in familiar places (Russell, the farm) and unfamiliar (a guinea pig). We travel to the war front and read the letters Otto painstakingly writes to Etta, who’s teaching him to spell.

We learn how much Russell loves both Otto and Etta and how deeply it affected him that he couldn’t fight. We understand why he goes to find Etta when Otto doesn’t.

I won’t tell you about James. He’s a pleasure that should be come across in the course of reading this magnificent and quietly powerful book. Hooper’s understated, rhythmic language tells you just enough to feel like you’re there. “She had been in Manitoba for three days, three dry days, when Etta’s boots started leaking. Not letting liquid in, but letting it out, leaving a rust-colored trail behind her.” And this: “When their ship pulled ashore, seven days later, all of Otto’s hair had gone white, like the seafoam, like the bones of the fish they had every day for dinner and supper, all of it pure white.” And this: “One of the cows sighed, a heavy sigh with the weight of a cow. Russell stepped over and ran a hand along its back. Etta, he said, you’re wearing strange clothes.”

I mentioned magical realism. Some of the most important events in the book may or may not have happened. It only makes the story feel more real, the way our own stories change and pulse in our minds until we can’t quite remember exactly what was said, exactly how the dream ended. Emma Hooper’s novel is very unlike other novels, to its benefit. The book is like finding a box of someone else’s saved treasures: some of them speak plainly and others remain mysterious, but all point you toward the truth of the person who unwittingly shared them with you.