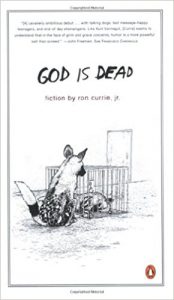

God Is Dead, by Ron Currie, Jr.

God Is Dead

Ron Currie, Jr.

Penguin Publishers

Four stars

Reviewed by Jessica Gribble

When you start with the premise that God is dead—actually dead, not just dead in a Nietzschean philosophical way—you’d better deliver. Happily, Ron Currie, Jr., has delivered a terrific novel, full of dark humor and moments of tenderness. It’s an uncomfortable book at times—I kept wishing that its events didn’t seem so darn likely. Currie has said that God Is Dead was written in the spirit of a line from The Brothers Karamazov: “If God is dead, then everything is permitted.” Permitted or not, when the citizens of the world learn that God has come to earth disguised as a young Dinka woman in the North Darfur region of Sudan and subsequently been killed, they create and join armies, kill each other, and worship their children. Interspersed among the eerily familiar actions of jaded teenagers and suicidal priests is a dog that has eaten some of God’s dead body and can now talk.

Each chapter of the novel is a separate short story, but together they provide a coherent view of the world after God. By the end of chapter one, you know what you’re getting into: Colin Powell spends a lot of the chapter making inflammatory remarks about George W. Bush. In hip-hop language. The rest of the nine chapters include a suicidal priest; a teenage suicide plot; parents who worship their children; an alcoholic son with a capable father; an interview with the last dog from the feral pack that ate God’s body; war combined with the text messages of an angst-ridden teenager; a brother living with the reality and motivation of his brother’s crimes; and more war, bleeding into scenes of Americans with their heads figuratively in the sand.

As I suppose we can now expect from hot young writers, a quick google of Ron Currie, Jr., leads to his MySpace page. We learn that he’d like to meet Julian Lennon, Ziggy Marley, Jeffrey Jordan, Jean-Michel Cousteau, George W. Bush, Jason Bonham, and Joe Buck: the sons of famous fathers. Though Currie protests in an interview that—unlike so many first books—this book is not about the family, he handles families deftly. God Is Dead is dedicated to his dad and Currie is an acute observer of the tensions and deep feelings between parents and children.

The desolation and hopelessness are Kafkaesque. However, the writing is alive, and the relationships hum with authenticity, poignancy, and sometimes redemption and humor. Currie’s visual details are stark, cleanly drawn, and memorable: “He’d dropped the grim weight of his book bag on the ground, where the sand was still wet from high tide, and when he slung the bag over his shoulders for the walk home it would be damp against his back and stink of dead clams.” Currie uses language sparingly, neatly—there are just enough words to set the scene. He’s not afraid of life being a bit mysterious. You read on the edge of your seat; what will happen? Will they kill each other? Will the dogs die? Will the light and easy life of a good kid turn dark?

You’ll pick up this book because it says “God Is Dead” right on the cover and it’s a thin first novel with an impressive list of quotes singing its praises. When you pick it back up to read for the second or third time, it’ll be because you’ve been watching the news and life seems black, bizarre, and filled with nervous hilarity. You’ll want God Is Dead to help you remember that the lightness of hope can float, somehow, on the sea of despair.