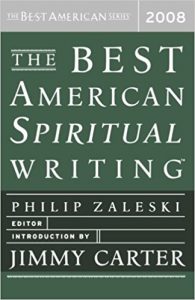

The Best American Spiritual Writing 2008 edited by Philip Zaleski, Introduction by Jimmy Carter

The Best American Spiritual Writing

Edited by Philip Zaleski, Introduction by Jimmy Carter

Houghton Mifflin Company

Four stars

Reviewed by Jessica Gribble

One of the pleasures of The Best American Spiritual Writing 2008 is its inclusion of poetry along with essays. Another is Jimmy Carter’s introduction, which is both thoughtful and concise. He talks about the power of both words and The Word, capturing both his personal Christian spiritual life and the broader, inclusive spirituality that infuses the selections in this collection. In fact, this is a defining characteristic of this book—its poems and essays are both personal and universal. Americans think of themselves as a religious people, but the foreseen intolerances of doctrinal Religion scare away many an educated reader. This book includes essays by and about people who hold fast to particular religious traditions—Catholics, Jews, Lutherans, Zen Buddhists—but it also includes essays and poems on current events, science, and nature.

I had just finished reading this slim volume when John Updike died. I didn’t think much about his death beyond a sense of sorrow at the passing of a noted literary genius, until I sat down with the table of contents of Best American Spiritual Writing to begin this review. I remembered reading the work of some favorite authors of mine—Natalie Goldberg, Maxine Kumin, Oliver Sacks—and then I noticed John Updike. I went back to what turned out to be his poem, Madurai. I had read it along with everything else, in one fell swoop. After his death, it seemed like a fitting spiritual act to go back and take a closer look. I immediately noticed the rhyme scheme. After some poking around through my library of books on writing, I found the one that would help me decipher the form. It turns out that Madurai is an English sonnet. Further, my book informs me that “Stanza 1 (the octave) presents a situation or a problem that stanza 2 (the sestet) comments on or resolves.” I won’t give away the whole poem, but the problem is “what is the point of life?” So you see, this poem, and this book, tackle the most important questions of all.

I was pleased to read two essays about Einstein—his ideas still have great relevance for both science and spirituality. (I was also pleased to see the quote “God does not play dice” only once.) Other topics include home schooling, family, holidays, transcendent moments, Reinhold Niebuhr, orthodoxy, Zen koans, Shingon Buddhism, belonging, hope, death, Chinese Christianity, atheism, mental illness, miracles, crime, quantum mechanics, Intelligent Design, Holocaust denial, lots of nature, and more. There are moments of great confusion, great peace, and great anger in here, just as there are in life. I found some of the essays and poems dull and/or incomprehensible. Some essays and poems I found marvelous, beautiful, important. I suspect that I could read this collection several times and change my mind about what mattered to me each time. There’s no question, however, that I would find something that mattered. There are so many ways to believe and experience both religion and spirituality that a collection of this kind is a wonderful idea. And Philip Zaleski has done an admirable job with the hard task of choosing a wide variety of writing. Some stories confirm our own beliefs and others open our minds to the beliefs of others. Anyone who wants to be challenged by the important questions in life will enjoy this book.